Short version: I’ve been getting into minimalism lately. On the flight back to Oxford I read Goodbye, Things: The New Japanese Minimalism by Fumio Sasaki.

Long version:

Minimalism

Minimalism is most simply the practice of attempting to minimise one’s possessions. Minimalism, and its popularity, is a response to the suffocating clutter many people experience. The cost of producing many items (clothes, appliances, toys) has fallen, and marketing to consume these items has become more prevalent and sophisticated, resulting in consumption beyond individual’s needs and capacity to manage possessions. Like many cultural phenomena, it is not merely a pragmatic solution to a problem, but also manifests as a set of values and an aesthetic (of which Apple Stores are an often cited example). Some of these are potentially problematic; A New York Times opinion piece opens with “[minimalism] has become an ostentatious ritual of consumerist self-sacrifice“.

My Experience with Minimalism

I have a natural urge to collect things. I inherited a sense of scarcity from parents who have escaped times of political upheaval. I detest waste, and find it easy to see potential uses for many items that ultimately I never use (scrap pieces of paper that might be handy to put down a note, packaging that might be used to carry something else someday, old electronics that I could strip for useful parts). The result is an ever growing collection of possessions that take both physical space and organisational time.

The mental problem I have with clutter is more significant. It is upsetting to wake up, and come home, to a growing pile of physical objects that correspond to tasks left undone. Books that would be nice to read, models it would be fun to build and paint, even an ever-thicker envelope of receipts that would, if analysed, give me insight into my spending habits (how much did I spend on cheese in 2017?). As this pile grows so does my sense that I am not in control of my life; if I were, wouldn’t I be able to get all these tasks done? “Maximalist” clutter becomes the physical representation of my poor time management and lack of drive. On each passing glance over this reminder, I am made a little more anxious, and my willpower is slightly sapped. Putting off those tasks trains the terrible habit of procrastination.

Minimalism provides an escape. By ascribing to the philosophy I am forcing myself through the discomfort of casting away what I perceive to have relatively low value. Through this I rid myself of the negative emotions that come from feeling out of control, and ultimately I find more time that is more comfortable. My first experience of this minimalist joy was moving to Oxford with only a suitcase of possessions. Suddenly, without distractions and incomplete projects surrounding me, I was more free to explore my new surrounds, to step up and tackle projects like this website.

Where I take issue with minimalism, particularly at the more extreme end (e.g. Fumio Sasaki’s), is the impracticality and expense. Ultimately you are outsourcing clutter to others, for example cooking and transportation. Food is a necessity. It is more affordable and often healthier if prepared from simple ingredients bought in bulk (e.g. flour, market vegetables). It is impractical to shop for food daily, and so storing groceries, the kitchen appliances needed to cook, and utensils to serve meals, are very practical anti-minimalist behaviours. Similarly while uber and bike sharing schemes can be convenient, owning and maintaining my own bicycle is cheaper and more pleasurable to ride.

Minimalist Book Report

I was given Goodbye, Things by Fumio Sasaki for christmas in 2017, but only set aside time to read it while flying. In five chapters it summarises the authors experience in finding minimalisim, discusses the development of the problems he feels minimalism solves, lists tips on adopting a minimalist lifestyle, gives examples of ways in which minimalism has helped the author, and concludes with some brief notes on happiness. I found the individual experiences relatable, but the historical and philosophical arguments less compelling. The many short guides in Chapter 3, “55 tips to help you say goodbye to your things, and 15 more tips for the next stage of your minimalist journey” become repetitive, but I feel there is value in explaining the same concept in a number of different ways as different readers will find some phrasings easier to digest than others. Ultimately, minimalism has clearly benefited Sasaki and helped him find a coherent identity, and as such he provides useful advice to aspiring minimalists. The mix of quoted individuals in Chapter 4 (Steve Jobs, Einstein, Lao Tzu, Tyler Durden) reveal an attempt to put minimalism on a cultural pedestal that I find unconvincing. I am left feeling minimalism is a useful tool, but a shallow philosophy.

Marie Kondo

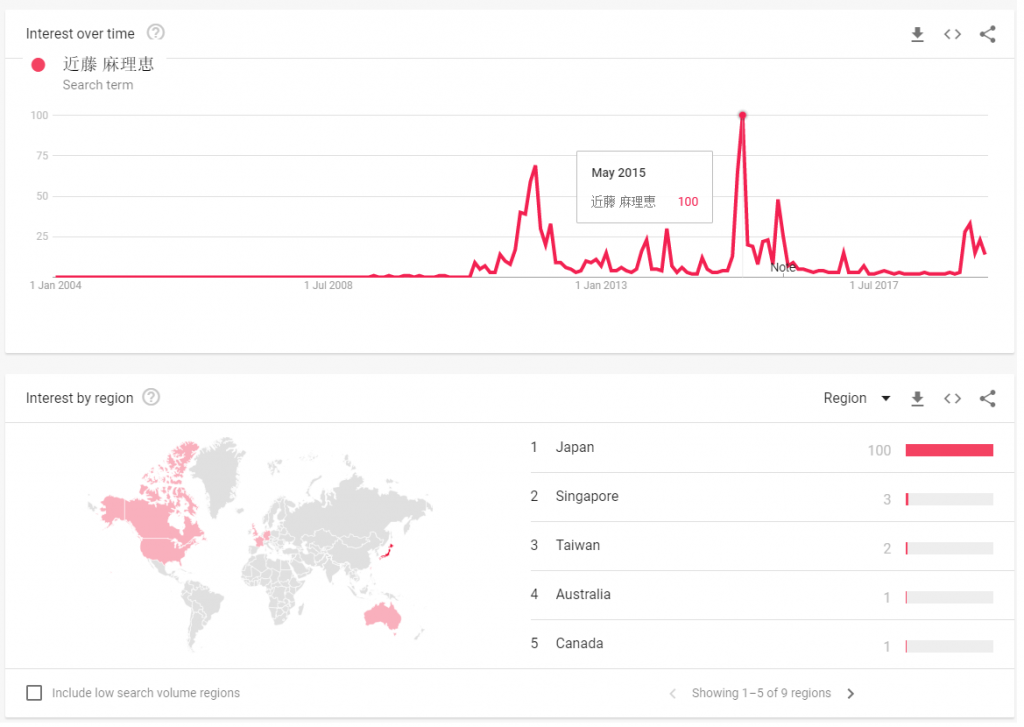

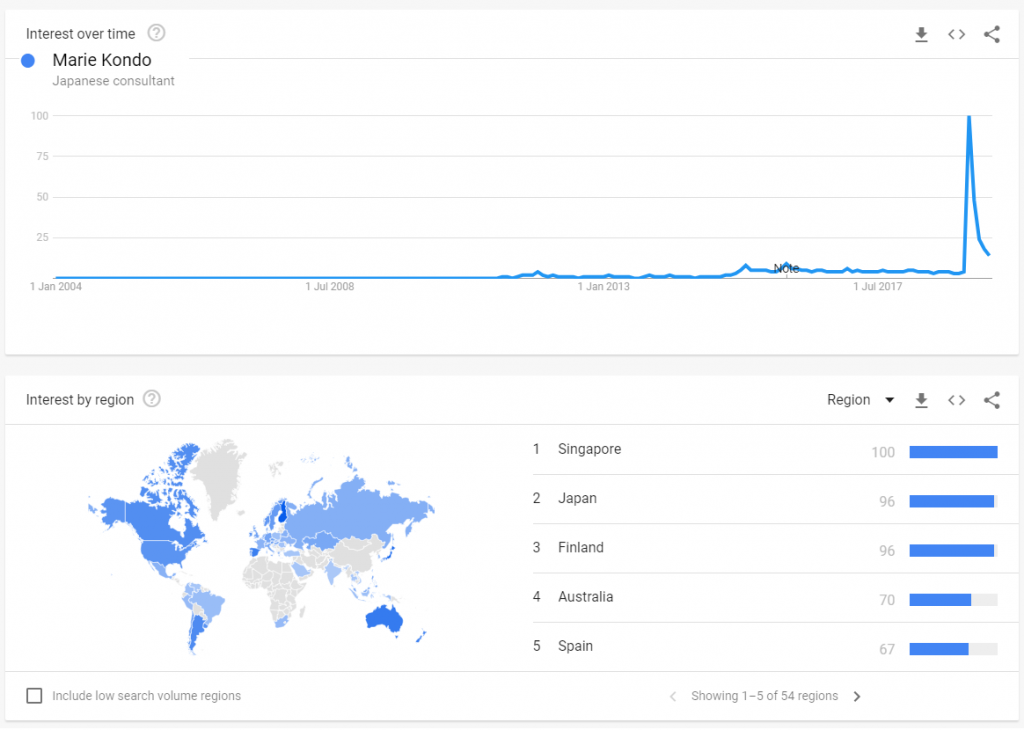

The face of minimalism, via her Netflix series, is Marie Kondo. Sasaki talks about Kondo’s influence on minimalism in his 2015 book, pointing out that her recent fame in the English speaking world was preceded by much earlier interest in Japan. Google trends supports this chronology. On the left in red, the search trends for 近藤 麻理恵 (Marie Kondo in Japanese) peak in December 2011 and May 2015, corresponding with the release of her book and being listed in the Time 100 most influential people respectively. Search trends for her name in English peak in January, with the release of her Netflix show.

Photo from the Week