The unstructured time in Managed Isolation has given me time to consider a range of questions. The most time consuming are the logistics: where am I going to live? What forms of transport will I be using? What type of work am I going to do? This in turn leads to other less tangible questions: What should the price of housing be in an ideal world? Why are road bicycles more expensive than entry level motorcycles? There are also more general questions from world news: Why is there so much scepticism about vaccines? What does the Gamestop saga mean for investing? Should governments be able to revoke citizenship? Is Google evil, and if so when did it become so? My hope for the coming months is to do some longer writing trying to improve the answers available to questions that interest me. For now, more trawling property classifieds.

2021 Week 6: Slow Learner

As I reflect on the last week of Managed Isolation and Quarantine, I realise that I have once again overestimated my free time in a period without formal work obligations. Despite repeatedly over committing to weekend activities and holiday to-do lists, I have not managed to learn to be conservative about my expectations of time off. When times are busy, side projects and nice-to-dos are easy to set aside, drifting lightly on their low import into amorphous blocks of time like these two weeks of hotel confinement. Having arrived here, the actual number of tasks I’d like to accomplish is overwhelming, and without clear hierarchy. Friends are kindly advising me that after an intense 3 years at ONI, a little seemingly unproductive rest is actually the most productive thing I could be doing, but those sensible comments pale compared with the guilt at not accomplishing what I set out to do. Perhaps next time I will remember this reality, having written about it in place of the topics I would have liked to explore given more time.

The outdoor exercise area at the Grand Millennium Auckland

2020 Week 34: Extreme Ownership

This week I shared some thoughts on the book Extreme Ownership.

I’ve been doing some 30 Year Thinking, and after some difficult conversations I condensed one aspect of my personality: I enjoy asking difficult questions. I like to poke and prod at an idea, sometimes callously, in a relentless search for truth. I want to understand why. That energises me, where it might drain others.

Photos from the Week

2020 Week 26: Find what you look for

The first half of 2020 is coming to an end, a time to assess progress on personal goals (or KPIs or OKRs). One personal goal was to write shorter weekly posts in favour of longer irregular posts. The 3 times I’ve succeeded in writing longer posts so far are A note on fear and death under the current pandemic, Lady Astronaut of Mars, and Productivity Update February 2020. I’ve been learning a little about funnels, and think that this might be a useful model for planning such posts in the future.

A side effect of science

As scientific research on SARS-CoV-2 is published, the general public is becoming more aware of preprint servers, redaction, and the messy side of science. I have not kept up with the deluge of publications, but a few friends have been asking for my opinion on some headlines. I shared the following observation:

As universities shut down, scientists saw the opportunity to return to doing research (which they enjoy) by studying SARS-CoV-2 in their field. Hypothetically, a group that studies kidney disease, might look into the effect of COVID-19 on the kidney. It’s improbable that a respiratory disease improves kidney function, so if an effect is observed it is probably detrimental. The likely result will be a publication linking SARS-CoV-2 and kidney deterioration. It may well be the case that common strains of corona-virus or influenza (or any illness) have a similar negative effect on the kidney that, under normal circumstances, would not be of a sufficient magnitude or interest to investigate. In this way, scientific publications and the resulting mainstream media headlines might cause undue alarm simply due to the unusual focus of the entire scientific community on a single disease.

By a similar mechanism to over-policing, intensive research focus can make a disease seem worse than similar, less investigated diseases. Be careful what you look for, you might actually find it.

Quote I’m Pondering

You cannot hope to build a better world without improving the individuals. To that end each of us must work for his own improvement, and at the same time share a general responsibility for all humanity, our particular duty being to aid those to whom we think we can be most useful.

Marie Curie

As a People Growth Engineer, my personal interest in self improvement is now linked to my professional responsibilities. ONI, through democratising life science research, is building a better world, but for us to achieve this we need to improve as a company, and therefore as individuals. Personal development and self improvement can feel selfish, but along with observing Curie’s duty “to aid those to whom we think we can be most useful”, individual improvements do lead to a better world for all.

Photo of the Week

2020 Week 24: New Normal

Tomorrow face coverings will become mandatory on public transport in England. The world is emerging from the shutdown caused by a pandemic. Harvard experimental scientists are returning to their labs. I feel remarkably unaffected: I commute by bicycle, my work continued through the pandemic, my hobbies occur at home or in nature. I have seen those around me grow more eager to return to normal, but for many that may never happen.

Hesitate less – the lesson I’m trying to implement now

“I have not slept. Between the acting of a dreadful thing and the first motion, all the interim is like a phantasma or a hideous dream. The genius and the mortal instruments are then in council, and the state of man, like to a little kingdom, suffers then the nature of an insurrection.” (Julius Caesar 2.1.63-71)

I am noting when I hesitate, and attempting to hesitate less. Some decisions are better made after investing time to carefully consider the choice, particularly decisions where the costs are high, but many tasks are made more daunting by postponing them. Fear and doubt build, and the cost to act increases. To get more done, I ought to act with more urgency.

Some things to share:

Books and Blogs

How to choose what to read, or listen to, or discuss? What ideas ought I visit (and subsequently consider, and sometimes write about). It is impossible to read everything. Roughly as many books fit in a shipping container as there are days in 100 years, and content comes in many forms beyond text. In this time of ubiquitous technology and physically distanced communication, each interaction begins with a choice of what content to consume, who to connect with. In a moment I could reach out to someone new, or call a close friend, or read the words of an author long dead and buried. Dwelling too much on that choice might lead to choosing nothing at all (see hesitation above), but making the right choice seems so important.

Too often I choose randomly. Occasionally I come across an abandoned blog, such as “Where’s my backpack?” and I want to study it, fearing the hosting will expire and the content will be lost (though archives of the web exist). On one rare instance I came across a blog and found myself. Part of why I write this blog is to refine and condense my thoughts, but as I approach my 100th post it becomes difficult to recall which topics I have already visited and what I have said about them. Simply to read my own words (of varying quality) now takes significant time. If in this moment your choice was reading my words, thank you, and please share your thoughts with me (my email).

Coffee as a hobby

Manual espresso coffee making process: I don’t use a PID (proportional-integral-derivative) controller, but otherwise my process is pretty similar.

Photos from the Week:

2020 Week 15: Growth amid Crisis

This has been another week of excitement, exhilaration, and exhaustion while working on SARS-CoV-2 projects at ONI. Doing experiments directly related to the pandemic is motivating, and I have noted that I find it easier to work 80-100 hour weeks on this project than 60-70 hours weeks on previous projects. I am very thankful to work with such an inspiring team, as well as to live with supportive friends. In the fourth week of this project, the sustained effort is also made possible by prioritising good diet, regular exercise, and making time for reflection and meditation.

While my week is dominated by the pandemic, I’ll share three moments unrelated to COVID-19. As I was drafting this post, I had a failure of discipline and did not get it out on time. I shared my new job title on LinkedIn. I attended an online interactive performance of The Tempest.

Practise Finishing or Practise Failing

The problem:

This post is a day late. I am disappointed, having managed to deliver on time for the past several weeks, and I felt the resulting introspection was worth sharing. I had enough time to write when I returned home on Sunday evening, but found myself falling into bad habits of procrastination I had hoped were gone. Surprisingly, the lack of resolve came not after a day of exhaustion, but one of relaxation. A day of Easter feasting, an absence of physical training, and only minimal experimental accomplishments left me lacking confidence to express my thoughts. When I could have been writing, I squandered time to distractions like YouTube and chess, sacrificing both a timely post and precious sleep.

A potential solution:

I have noticed a psychological benefit from completing 30-60 minutes of intensive indoor rowing. There are several points (usually at around 7 minutes and 20 minutes in) during these efforts where the temptation is to give up and stop rowing. The spartan rhythm of the exercise, and the absence of visual stimulation, are a backdrop for a battle between falling to weakness of will or building strength of discipline. I have found that days where I see the piece to the end, I am not only rewarded with exercise-induced endorphins and the satisfaction of completing the session, but also I find it is easier to see other tasks in my day to completion. Likewise, if I quit before finishing, it makes failing other tasks more likely. Either practising pushing through pain, or practising giving up when things are hard, reinforces the behaviour. Knowing this, I can focus on succeeding in the present moment, spurred on by recognising it will make the right choice easier in future. This knowledge also feeds into setting appropriate goals: goals which are impossible guarantee falling into a negative feedback loop.

Where else I want to apply this:

There are many brief moments through the day when I could learn a little, or train a little, or communicate better, or help someone. Sometimes I make the right choice, but often I throw that moment away in favour of consuming easy content (e.g. checking sales at an online store) or narcissistically checking for “likes” on social media. I should recognise that by building better habits around these moments, I will find it easier to do the better things. A little discomfort now is worth the behavioural change in the end.

People Growth Engineer

This week I announced my new job title as “People Growth Engineer”. Given the current pandemic related work, I am still applying my skills in the laboratory, but eventually the role will see me focus on the people of ONI rather than wet bench experiments. I am excited at the opportunity to contribute in a new way, driving growth throughout the organisation. I like that the unique title reflects my own passion for a scientific approach to continual learning and personal development. Specifically, the growth I will be engineering for ONI exists in three overlapping areas:

1. Growing the team through identifying the right people to join ONI.

2. Growing existing ONIees (ONIemployees) through individual skill development.

3. Cultivating a culture and fostering a common mindset that allow us to achieve our mission.

More detail to come as I transition into the role.

The Tempest

Over the long weekend I attended Creation Theatre’s performance of The Tempest via Zoom. I thoroughly enjoyed the interaction with the audience and actors, and the fun retelling through modern technology. Initially I was sceptical about setting aside time in this busy period for a play, but the life and laughter I took away from it gave me more joy than I would have expected from any other down-time. The actors involved the audience as Ariel’s spirits, acting out Prospero’s magic. Seeing other audience members on their web-cameras provided a good substitute for in person socialising in this time of social distancing. The humour could be a little cringe worthy at times, but taking Shakespeare playfully feels both authentic to the spirit of the comedy and makes supposedly high culture more accessible.

Photos from the Week

Subscribe to the blog

2019 Week 52: Retrospective Part 2

Short version: Thoughts on this year’s blog, and what is to come next year.

Long version:

Climate Catastrophe

Sydney, Australia, has a world famous fireworks display to mark the new year. This year, due to raging bush fires, there has been a call to cancel the display. This could only be symbolic, given that the contracts had been signed and the money paid. The fireworks went ahead. I think about the framing a former PM used, that climate change is “the greatest moral challenge of our generation”. That was 12 years ago. While a lack of economic literacy leads to the idea that the costs of the fireworks show could somehow be redirected to fight the fires, it is a deeper problem in human nature that allows the cost of dealing with climate change to grow impossibly in the future, rather than taking less painful action today. I feel another man made disaster gripping Australia, the obesity epidemic, to have similar roots.

It is difficult to think about the end of a year and the start of a new one without thinking about the scale of the challenges ahead. This briefing highlights how quickly time is running out to cut emissions. With governments in power across the English speaking world that so effectively wield tools of misinformation, I fear for our collective ability to make the right decisions. They are uncomfortable choices to make, but the consequences of ignoring them are going to be so much worse.

Reflection on 2019 Blog Posts

At the start of 2019 I wrote that “Last year I managed 11 posts out of 52 weeks for a 21% success rate.” It makes me proud to have hit “publish” for each week of 2019, though many came late. In total the posts came to a little over 30,000 words. They lack the quality and coherency of a novel or a thesis, but it has been a learning process, and reflects many of the topics I thought about in the last year.

Some favourites included:

In Week 38 I looked at the carbon costs in consuming New Zealand apples in the UK, which alongside Week 4 (on plant vs animal protein) are the two posts I’ve most often shared over a meal. Scientific content peaked when I focused on sharing papers, such as Altmetric in Week 8 and cover pages in Week 29. In Week 39 when explaining microwave ovens, I painfully came across the perfect article only after I had written most of the content. The data set I used writing about consumption in Week 48 was the most fun to explore.

Goals for 2020 Blog

The amount of content on berglabs as a whole has increased at least 5-fold in the last year. A reorganisation is due. It’s not easy to find content on the blog. Certain themes, like nutrition, or summaries of academic work, could be better grouped. I hope to reorganise the tags to make things a little easier to find. I aspire to write longer more coherent pieces, but cannot sustain that weekly, and so perhaps a monthly or quarterly essay to give more time to go deeper into a topic. A projects page may help me find collaborators, or pitch ideas that I would like to see in the world (inspired by Kevin Lynagh). I’ve also been toying with a page dedicated to people I think should be on pedestals, and a page announcing my values, the few things I believe to be clearly “good” or “bad”.

Photos of the Year

(click to expand)

2019 Week 48: Consumption

Short version: This Black Friday weekend is a relevant time to attempt to press my thoughts on consumerism into a post. A revealing ONS data set about household spending. Also some thoughts on blogging and whales’ heart beats.

A note on structure

On top of a tangled set of thoughts about consumption, there was a lot of interesting content to read, listen to, and watch on this topic. The structure of this post suffered, and so if you’re just here to skim I suggest scroll down to the bottom and just check out Trends from the data and Whales’ Heart Beats.

Consumerism

I want stuff. Lots of people also want stuff. Often, if they can, they go out and buy stuff. This is a simple thought, but the many paths it leads down have been a tangle in my mind for some time. This post is an attempt to rectify the clash between the obvious value in markets and trade with the absurdity of waste (see the two videos below) in modern developed economies. This is highlighted by celebrations of consumerism that occur after Thanksgiving.

Chasers War on Waste

The true cost of fast fashion | The Economist

People want to be rich

I think it is reasonable to presume the overwhelming majority of people would like to have more money. Money provides security, safety, and freedom (and most of lower tiers of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs). Casey Neistat points out that for a lot of people, money will solve all problems. although people with plenty of money still have problems.

This simple desire for material wealth gets complicated by how different that desire looks at different points of time. The majority of people in the developed world have access to goods and services that were restricted to only the most wealthy only decades ago. Advances in agriculture and medicine mean even the poorest citizens have access to goods like pineapples and penicillin that would have been unimaginable to emperors and kings of centuries past. This Louis CK bit makes light of changing expectations. That desire for newer and shinier at the expense of appreciation for what we already have is, in part, created by the desire for companies to grow their sales and profits. An array of narratives are pushed through advertising. A particularly disturbing yet powerful lie is that you can change who you are simply by owning something. The idea that you can be fitter/sexier/smarter by buying something, rather than by learning or growing, sells a lot of products, despite failing their buyers.

School of Life: History of Consumerism

Black Friday

Black Friday is a day of discounted selling by retailers following Thanksgiving Day, which is observed by shops throughout much of the world. Scenes of people rushing into stores and fighting over relatively cheaper items are symbolic of a period of significant spending by consumers as the end of the year, and particularly Christmas, approaches.

A lot of people work in retail. In Australia, it is 1.3 million, nearly 10% of the labour force. This is an enormous amount of human life dedicated to the mere act of selling things (1.8 Australian lifetimes is spent per working hour by the collective in shops, life expectancy in Australia = 82.5 years). Intuitively (and so simplistically as to be utterly inaccurate) this struck me as a waste of time, given retail exists as a middle man between producers and consumers. Of course in reality at points retailers make the entire system more efficient (for example by collecting fruit and milk in bulk and distributing it to stores in lieu of each consumer visiting a farm individually), but in practice profit incentives drive this enormous work force to motivate us all to consumer more.

One way consumption is driven is through pricing. The decision to purchase an item is in part determined by the price attached to that item. Commonly items are priced at X.99 rather than X+1, because that centipoint increase is far more psychologically significant than the additional profit. A further extreme of this is quantum pricing where fewer price points mean profit margins are obfuscated. The discounts of Black Friday create the perception that shoppers are saving money by buying things at a lower price than they would otherwise, combined with a false scarcity that this is the only time to buy. In reality most consumer goods depreciate rapidly so any future time is a better time to buy. Less scrupulous stores raise prices before the sales only to mark down to pre-sale prices. One clear sign of the power of this frenzied overconsumption is the willingness for people to take on debt to purchase luxuries. Loan Sharks take advantage of Black Friday pressures to consume.

Interesting observations from some actual data

A few weeks ago I came across the BBC series “My Money“, which takes individuals and looks at their spending over a week. My fascination with how other people spend money stems from not having a good answer to “What is the appropriate/correct/optimal amount to spend on X”. There are intuitive answers to this, which is why spending £100 a week on cheese or £5 a quarter on electricity “feel” high and low, but that intuition is shaped by our relatively limited insight into other’s spending (likely dominated by our parents’ and partners’ habits) augmented by the media we consume, particularly the coercive forces of marketing.

I am consistently frustrated with the concept of normal. There are no “normal” people in the same way there is no way to roll 3.5 (the centre of the normal distribution for values) on a 6 sided die. This video featuring wrestler John Cena emphasises the difficulty in describing an “average” american. However discovering the UK’s Office of National Statistics collects and compiles data on household expenditure (among other things), and produces reports on the distribution of spending, provides data on where the distributions actually lie. I found exploring the data fascinating. I was particularly excited to find this data set breaking down typical weekly expenditure by item in pretty specific categories (e.g. “Cheese”, “Books”, and “Package Holidays – UK” are separate categories).

Here are some observations:

The big picture: income and expenditure

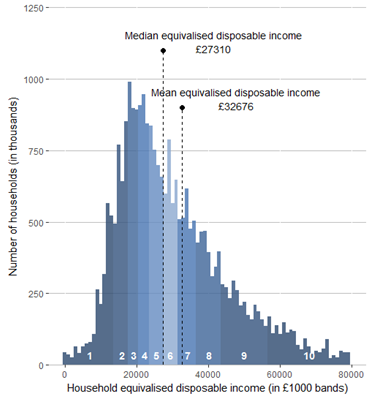

The distribution of incomes in the UK gives an insight into what households can actually afford.

The interactive graphic below gives insight into how the typical UK household spends (taken from this ONS report).

Trends from the data

General trends

A wealthier decile has more people per household.

Wealth increases steadily between the 2nd and 8th deciles, and sharply at both ends.

Overall spending trends

Spending in most product areas correlates with increasing disposable income on both a per person and per capita level.

Interesting specific spending trends

Food

Poultry (strongly) and beef (weakly) correlate with increasing wealth, pork and lamb are flat across groups, and bacon and ham have a weak negative correlation.

Housing

Poorer households spend proportionally much more on housing, making up 19.1 % of spending for the lower half of households, vs 11.1 % for the upper (I guess this is because of renting vs owning). This is after accounting for housing benefits to the lowest deciles.

Transport

Transport spending is correlated with income, with a sharp increase in the top decile due to the purchase of new (presumably luxury) cars.

Clothes

In the bottom three deciles women spend 2.5x more than than men on clothes, whereas that ratio is only 1.3x for the top decile.

Only the top few deciles use drycleaning services.

Alcohol and Tobacco

Spending on alcoholic drinks was correlated with income, but the trend was dominated by wine, while beer and spirits were fairly independent across the groups.

Lower income deciles spent more per person on tobacco and other narcotics.

Health and Education

Education (school fees) and sports subscriptions (gyms) correlated strongly with income.

Entertainment

There is a hump like feature in the audio-visual equipment categories in the 6th and 7th deciles.

Spending on hotels appears to have an exponential relationship with increasing disposable income.

Statistical definitions

Useful definitions from the ONS:

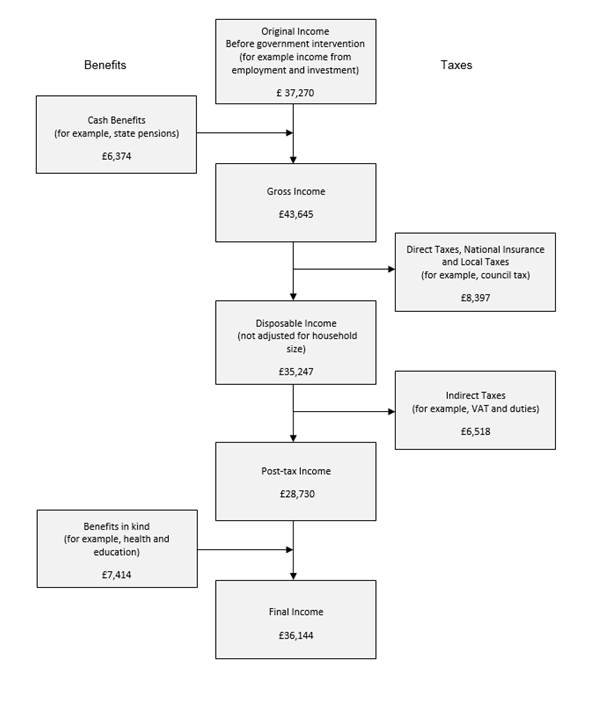

What is disposable income?

Disposable income is arguably the most widely used household income measure. Disposable income is the amount of money that households have available for spending and saving after direct taxes (such as Income Tax, National Insurance and Council Tax) have been accounted for. It includes earnings from employment, private pensions and investments as well as cash benefits provided by the state.

The five stages are:

1. Household members begin with income from employment, private pensions, investments and other non-government sources; this is referred to as “original income”

2. Households then receive income from cash benefits. The sum of cash benefits and original income is referred to as “gross income”.

3. Households then pay direct taxes. Direct taxes, when subtracted from gross income is referred to as “disposable income”.

4. Indirect taxes are then paid via expenditure. Disposable income minus indirect taxes is referred to as “post-tax income”.

5. Households finally receive a benefit from services (benefits in kind). Benefits in kind plus post-tax income is referred to as “final income”.

Note that at no stage are deductions made for housing costs.

Amusing group names:

While looking at consumer spending in the UK, I found the following categories that the ONS uses to divide UK residents. Some of them were incredulous to the point of being amusing.

Categories:

Rural residents, Cosmopolitans, Ethnicity central, Multicultural metropolitans, Urbanites, Suburbanites, Constrained city dwellers, Hard-pressed living

Sub-categories:

Farming Communities, Rural Tenants, Ageing Rural Dwellers, Students Around Campus, Inner-City Students, Comfortable Cosmopolitans, Aspiring and Affluent, Ethnic Family Life, Endeavouring Ethnic Mix, Ethnic Dynamics, Aspirational Techies, Rented Family Living, Challenged Asian Terraces, Asian Traits, Urban Professionals and Families, Ageing Urban Living, Suburban Achievers, Semi-Detached Suburbia, Challenged Diversity, Constrained Flat Dwellers, White Communities, Ageing City Dwellers, Industrious Communities, Challenged Terraced Workers, Hard-Pressed Ageing Workers, Migration and Churn.

Personal conflict: running tech

I like running, and improving my fitness more generally, I suppose because it helps me to self actualise. One of my personal weaknesses in fighting back against the commercial marketing machine has been in running tech. As such, I found this video from the New York Times both entertaining and helpful in realising the main thing I need to run faster is not a piece of equipment, but to simply run more and faster.

December blogging reflection

Lately I’ve been posting each week on Sunday come what may. There’s a pretty wide variance in how much time goes into each post, which is not always related to the quality of each post. Some topics I have a better understanding of before I start to write. Some observations are not insightful. Some posts go out unfinished.

Ideas vary in quality. Some ideas were probably not worth writing about at all, while others are so huge they could easily fill hundreds of pages. Not every idea is a good idea, and even a good idea poorly executed is not a good result.

Some topics deserve to be revisited, edited, improved, expanded etc. But writing in this weekly format is useful. Sometimes quantity results in quality. If I maintained a high expectation for each blog post I would write less, and my writing would not improve. Moreover in trying to write each week I am motivating myself to learn. I do hope to better organise myself in the next block of blogging (i.e. next year’s posts) to segregate space for tackling bigger topics less frequently, with a less structured more regular section.

As I was writing this post I received Peter Attia’s weekly email, describing his struggles with writing. It was extremely motivating to read words that felt so familiar they could have been my own. I would not wish insecurities on anyone, but it is deeply reassuring to be reminded those feelings are normal.

While on the topic of other writers; blogs I’d like to share:

Econometrics By Simulation: interesting applications of statistical software.

Beau Miles: Came across some of his films, the first content in a while to make me really miss Australia. Describes himself as “Award winning filmmaker, poly-jobist, speaker, writer, odd.”

Whales’ heart beats

A wonderful aspect of having scientists as friends is that they share exciting science with you that you would otherwise miss. One example is this paper about how the heart rate of blue whales changes as they dive for food. Their enormous hearts beat as slowly as two times per minute and as quickly as 37, which is about as fast as is physically possible. It also contains this informative figure, which I feel tells the story clearly and succinctly.

Photos from the Week

2019 Week 26: 6 Month Review

Short version: After attempting (and failing) to write a blog post each week for the past 6 months, I look back on those posts and reflect.

Long version:

Identity and Expectation

A realisation occurred to me whilst thinking about the unfinished drafts for this blog. Fitness, particularly competitive fitness, is not a core part of my identity, and so it does not threaten my ego to post slow times on parkrun. By being comfortable running slowly, I run more, and in running more, I run faster. Being comfortable with being a slow runner makes me a faster runner. The ability to understand difficult concepts, and to communicate effectively, is a core part of my identity. This means being unable to understand difficult concepts, and being unable to write well, does hurt my ego. If I am insecure about these aspects, I read fewer scientific papers, I write fewer blog posts, and the result is I do not improve in these areas. The lack of progress makes me more insecure, and a cycle of procrastination begins.

The solution, therefore, is to be comfortable with not understanding, or in the case of this blog, to be comfortable writing poorly. The purpose I have identified, in attempting to write each week rather than each time I have something interesting or insightful, is a need to practice writing regularly, not a need to demonstrate the skill of writing. To be able to write more regularly, I need to stay true to that purpose, and not be swayed my the desire to be interesting, insightful, or demonstrate a level of skill I have yet to achieve.

With that in mind I post this unfinished, and hope to take time when I am up to date to examine the first 25 posts of 2019, and identify what I have done well, and what I need to improve on, as I focus my efforts on more regular content in the 26 posts to come.

Posts I liked:

The short summaries of papers from Week 8 was fun to write, but regrettably shallow. Although not a weekly blog post, I was happy with my comprehensive first race report. Writing about diet and alcohol had a real effect in my life; it made it easier to hold myself to my decision in the face of perceived social pressure. I got stuck for a while trying to write about video games, but overcoming that was useful to me in understanding my relationship with that form of entertainment. Week 15’s Minimalism felt reasonably cohesive.

Posts I did not like:

The most common mistake I see in my writing is the use of unnecessarily complex sentences. Phrases like “much of the time” instead of “often”. I would guess the reasons for this are 1) a lack of consideration and technique, 2) attempting to be precise for fear of being misunderstood and 3) an affectation in order to appear intelligent. Ultimately the goal of writing is to communicate. To be succinct first requires the ideas themselves to be coherent, and testing my ideas by attempting to write about them has helped me think more clearly. In a limited time, some ideas never become coherent, and the resulting posts are much weaker. For example, in Week 21 I didn’t understand my own conclusions about marriage or Romania, and so I feel the writing suffered. The book report in Week 7 was never written, and I cannot help but feel a tinge of shame when I think about it.

Photos from the Week

2019 Week 15: Minimalism

Short version: I’ve been getting into minimalism lately. On the flight back to Oxford I read Goodbye, Things: The New Japanese Minimalism by Fumio Sasaki.

Long version:

Minimalism

Minimalism is most simply the practice of attempting to minimise one’s possessions. Minimalism, and its popularity, is a response to the suffocating clutter many people experience. The cost of producing many items (clothes, appliances, toys) has fallen, and marketing to consume these items has become more prevalent and sophisticated, resulting in consumption beyond individual’s needs and capacity to manage possessions. Like many cultural phenomena, it is not merely a pragmatic solution to a problem, but also manifests as a set of values and an aesthetic (of which Apple Stores are an often cited example). Some of these are potentially problematic; A New York Times opinion piece opens with “[minimalism] has become an ostentatious ritual of consumerist self-sacrifice“.

My Experience with Minimalism

I have a natural urge to collect things. I inherited a sense of scarcity from parents who have escaped times of political upheaval. I detest waste, and find it easy to see potential uses for many items that ultimately I never use (scrap pieces of paper that might be handy to put down a note, packaging that might be used to carry something else someday, old electronics that I could strip for useful parts). The result is an ever growing collection of possessions that take both physical space and organisational time.

The mental problem I have with clutter is more significant. It is upsetting to wake up, and come home, to a growing pile of physical objects that correspond to tasks left undone. Books that would be nice to read, models it would be fun to build and paint, even an ever-thicker envelope of receipts that would, if analysed, give me insight into my spending habits (how much did I spend on cheese in 2017?). As this pile grows so does my sense that I am not in control of my life; if I were, wouldn’t I be able to get all these tasks done? “Maximalist” clutter becomes the physical representation of my poor time management and lack of drive. On each passing glance over this reminder, I am made a little more anxious, and my willpower is slightly sapped. Putting off those tasks trains the terrible habit of procrastination.

Minimalism provides an escape. By ascribing to the philosophy I am forcing myself through the discomfort of casting away what I perceive to have relatively low value. Through this I rid myself of the negative emotions that come from feeling out of control, and ultimately I find more time that is more comfortable. My first experience of this minimalist joy was moving to Oxford with only a suitcase of possessions. Suddenly, without distractions and incomplete projects surrounding me, I was more free to explore my new surrounds, to step up and tackle projects like this website.

Where I take issue with minimalism, particularly at the more extreme end (e.g. Fumio Sasaki’s), is the impracticality and expense. Ultimately you are outsourcing clutter to others, for example cooking and transportation. Food is a necessity. It is more affordable and often healthier if prepared from simple ingredients bought in bulk (e.g. flour, market vegetables). It is impractical to shop for food daily, and so storing groceries, the kitchen appliances needed to cook, and utensils to serve meals, are very practical anti-minimalist behaviours. Similarly while uber and bike sharing schemes can be convenient, owning and maintaining my own bicycle is cheaper and more pleasurable to ride.

Minimalist Book Report

I was given Goodbye, Things by Fumio Sasaki for christmas in 2017, but only set aside time to read it while flying. In five chapters it summarises the authors experience in finding minimalisim, discusses the development of the problems he feels minimalism solves, lists tips on adopting a minimalist lifestyle, gives examples of ways in which minimalism has helped the author, and concludes with some brief notes on happiness. I found the individual experiences relatable, but the historical and philosophical arguments less compelling. The many short guides in Chapter 3, “55 tips to help you say goodbye to your things, and 15 more tips for the next stage of your minimalist journey” become repetitive, but I feel there is value in explaining the same concept in a number of different ways as different readers will find some phrasings easier to digest than others. Ultimately, minimalism has clearly benefited Sasaki and helped him find a coherent identity, and as such he provides useful advice to aspiring minimalists. The mix of quoted individuals in Chapter 4 (Steve Jobs, Einstein, Lao Tzu, Tyler Durden) reveal an attempt to put minimalism on a cultural pedestal that I find unconvincing. I am left feeling minimalism is a useful tool, but a shallow philosophy.

Marie Kondo

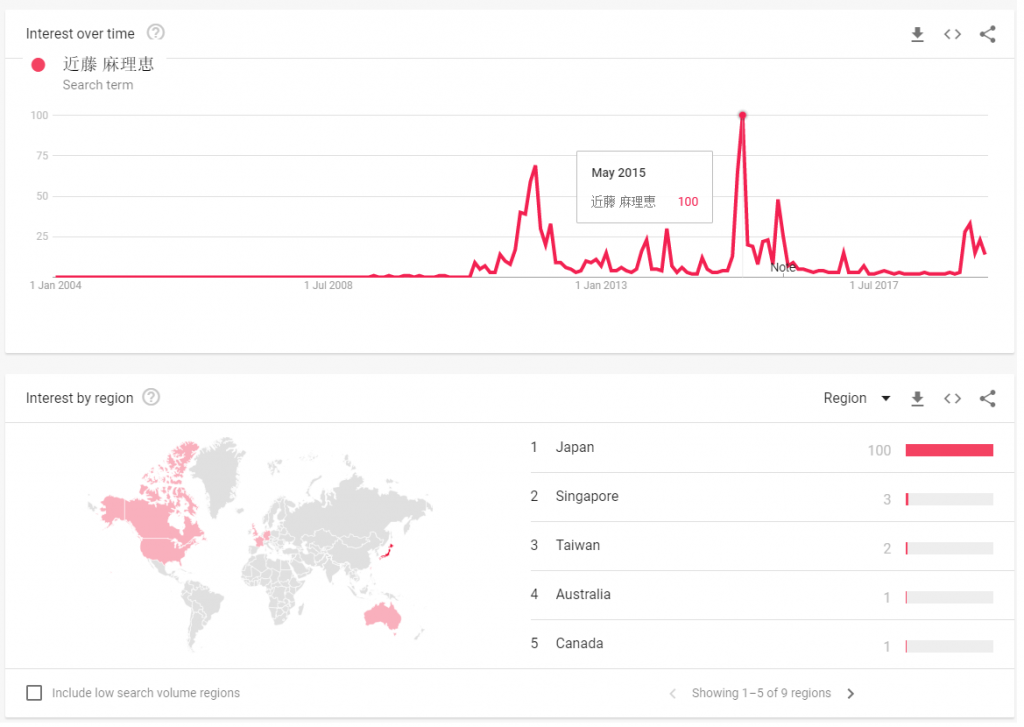

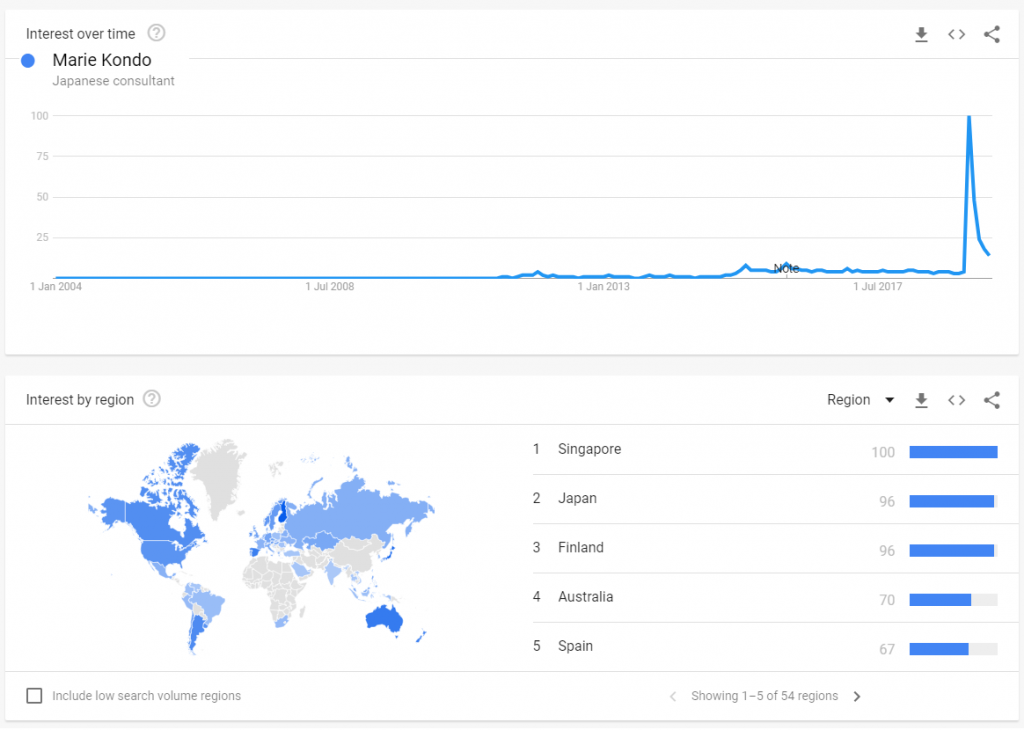

The face of minimalism, via her Netflix series, is Marie Kondo. Sasaki talks about Kondo’s influence on minimalism in his 2015 book, pointing out that her recent fame in the English speaking world was preceded by much earlier interest in Japan. Google trends supports this chronology. On the left in red, the search trends for 近藤 麻理恵 (Marie Kondo in Japanese) peak in December 2011 and May 2015, corresponding with the release of her book and being listed in the Time 100 most influential people respectively. Search trends for her name in English peak in January, with the release of her Netflix show.

Photo from the Week